Product design or industrial design is a big deal for any country. You know those labels you read on the back of a product? Maybe you’ve seen some that read Made in the U.S.A. Made in Switzerland. Or more popular, Made in China? All of these have a certain value and a different connotation to them, regardless of how good the product actually is.

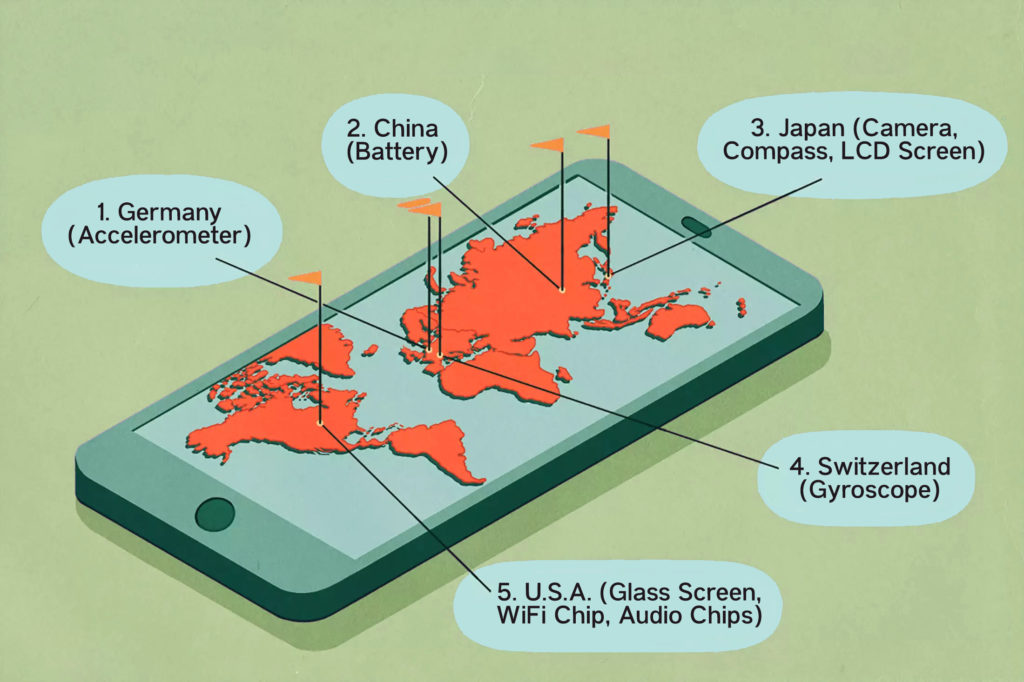

Now off the bat, you can tell which one has a negative connotation to it, but most products, especially technology actually have a very subjective creation story behind them. You see, most technology isn’t just MADE in a specific country. iPhones for example, that are quote, “made in China” are assembled in China, but could have some parts from Thailand, some from Europe, but was designed in California. So there are many outlets from which any given product is created.

China is looking to remove itself from that negative connotation, a push for quality that resembles a time when Japan sought out the same goal back in the 20th Century.

To understand what it was like for Japan, let’s scrub the timeline back, all the way to the beginning of World War II.

Japan was at the brink of war, the country’s quality measure of products was broken up into 3 tiers. Japan’s priorities were shifted at this time, so the lowest tier was Japan’s consumer goods that were exported to other countries, this is what led to Japan’s initial reputation of a subpar quality of goods.

The second tier at the time was the quality of military hardware and supplies, now this one was obviously important for Japan, so the military had its best engineers, materials, and its quality subsequently competed with other countries.

Finally, the highest quality tier was that of the ancient Japanese tradition of fine craftsmanship in handmade goods.

Let’s scroll the timeline back a little further to the 16th-Century. Dutch and Portuguese explorers had just reached the Japanese archipelago. Their discovery led to discovering Japanese crafts such as woodblock prints, paper, and lacquerware, among other products. These were found to be far superior to anything known in Europe.

This is what set the bar for what Japanese products were truly destined for: quality.

When Japan lost the war, it was clear that they were doing something wrong, and they sought out that change.

1954.

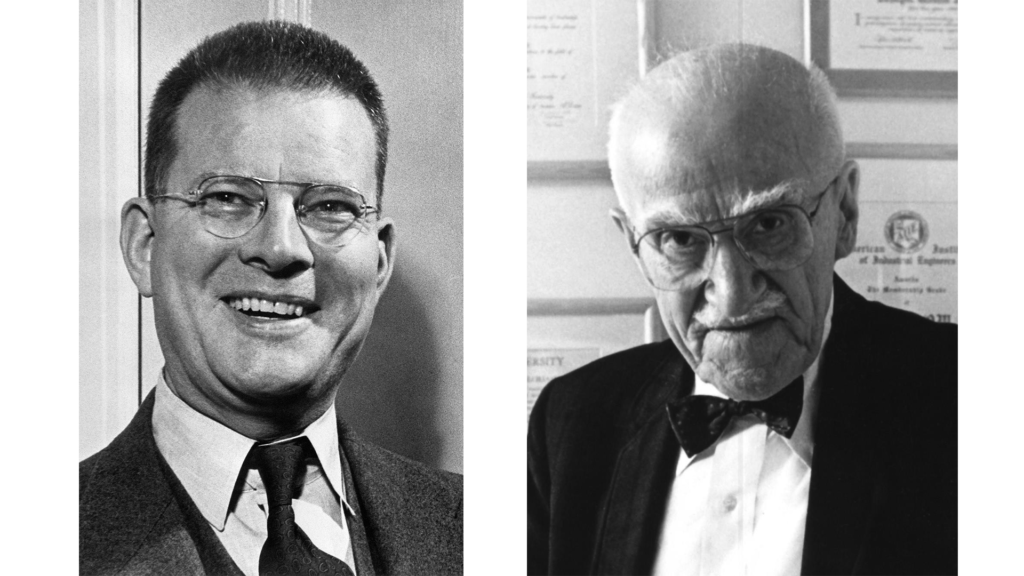

The Japanese Federation of Economic Organizations was held and two American men were invited. W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran, both engineers and management consultants in the U.S.

140 chief executives from the largest manufacturing companies in Japan attended. Juran tells the Japanese executives two key ideas that would change the way Japan viewed its products, created, and delivered them.

The first idea was quality management, this involved managing for quality by its design and how to inspect them for defects BEFORE it reaches the hands of consumers.

The second key idea was to analyze and supervise the manufacturing process. This solution allowed products to be seen as they are being created to locate the source of defects, fix them, which created a virtually defect-free product from the starting point.

Improving the production process improves the quality of products. Inspections require less work as they aren’t finding as many defects, so it works great in both ways.

And that is exactly where Japan honed in on. The birth of the Quality Revolution.

During Juran’s stay in Japan, he suggested that Japanese companies try to find ways for companies to train their employees on quality improvement and control. They listened.

This led to a full swing of a quality revolution. The senior executives of those very companies took charge of managing the quality. Listed on their business plans were quality goals, and each action headed directly into a sustainable lead in quality.

By the time the 1950s roared in, U.S. companies could not compete with Japanese prices for products, and this boom of Japanese quality later in the decade, caught U.S. companies completely off-guard.

One notable U.S. company that was thrown off immensely was the Xerox Corporation. It reigned in its golden years as a powerful company. Everybody wanted Xerox copies in their office but needed to lease a Xerox machine to get one. Executives of the company had many measures of metering sales, costs, profits, but nothing to show customer satisfaction. It was failing, as the machines would malfunction or completely break altogether, and regularly.

Xerox was able to acquire some insight on this matter but they made a poor choice, they created a service that would fix the broken Xerox machine. This didn’t sit well with the customers. They just wanted a product that was designed properly and wouldn’t need to be serviced from the get-go.

This same story occurred with other companies around the U.S., one prominent example was in the color television industry. In 1950, roughly 30 U.S.-owned companies were producing them, but by the ’80s only one company still stood.

This led Japanese companies to rush in, take action, and compete. In the 1950s, Japanese cars had such poor quality that they could barely be sold in the United States. After implementing the quality improvement method throughout the leading industries, year after year, it added up. And in 1975, after more than two decades of hard pushing through quality products, the Japanese leveled up with and even surpassed U.S. automakers in product quality.

What the U.S. once had, in terms of quality and the status most U.S. companies attained in the early half of the 20th century became battered. It was imminent for the U.S. to finally have competition but to the consumer’s benefit, competition leads to a greater reach among all companies and it creates better products from it.

As Juran puts it, “Our need is not to redesign our culture. Our need is to intensify what these companies have shown us what we can do.”

The phrase “Made in Japan” used to have a comparative connotation to subpar quality. But with Japan’s evergrowing improvement in its standards and persistence of change, it became one of many factors as to why Japan’s push for greater design evolved. To this day, Japanese industrial design continues to be a fundamental influence throughout today’s world.